At this year’s Karachi Lit Fest, Hanif Qureishi asserted that the purpose of such festivals was “to give writers a social life.” I concur wholeheartedly, but still I admit I was a little scared to go to Beirut and socialise there. This is because several Syrians had advised me to avoid speaking about the revolution while in the city, and to watch my back in areas controlled by Syrian regime allies. “They know who you are,” they muttered darkly.

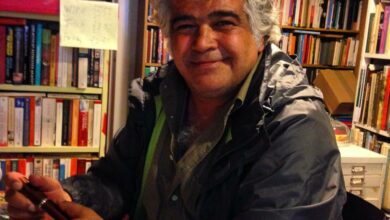

But I was fine. At no point did I feel under any threat. I presume the warnings tell us more about the fear so successfully planted in Syrian hearts than they do about the capacity of the flailing regime to hunt down obscure writers. True, one Syrian slit another Syrian’s throat outside the Yunes Cafe just a couple of minutes’ walk from my hotel one night. Reports varied as to whether the killing was personally or politically motivated. And true, writer Khaled Khalifa’s arm was still in a sling after being broken by regime goons during the funeral of murdered musician Rabee Ghazzy back in May. Khaled, whose most famous novel ‘In Praise of Hatred’ is about to be published in English by Doubleday (I’m writing the introduction), is a warm and gentle man who smiles irrepressibly despite it all. He spoke fearlessly during his event at the Hay Festival. He’ll be back in Syria now. In Beirut I asked him why he didn’t stay outside, in safety. He said he can’t, he becomes scared for his friends and family when he’s outside.

I spent one inspiring evening with a group of Syrian revolutionaries, supporters of the Free Syrian Army who confound the stereotypes propounded by the regime and picked up on by certain infantile leftists. Far from being Salafists and tools of imperialism, these were secular men and women (one of Christian background) sharing a flat and ideas, drinking whiskey and mate, reflecting on the surging movement of the recent past and checking internet updates on the immediate present. They were well-informed, intelligent, and nuanced in their thinking (at one point we discussed the nature of evil and the complex question of individual culpability). They had seen nasty things, yet talking to them made me surprisingly buoyant. They believed they were winning their fight.

I was introduced to the activists by the organisers of Reel Festivals, promoters of work from (so far) Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine and Syria. They are planning to do another Reel Syria Festival (the first was in London) in Beirut’s southern suburb, in Hizbullah territory. Hizbullah is repaying old debts to the Syrian regime by opposing the Syrian revolution (in my opinion it has committed an uncharacteristic and enormous blunder); its acquiescence to a festival which will provide talking space to revolutionaries, then, is another example of the party’s carefully studied tolerance.

Not far from the Syrians’ safehouse there’s a collective in a shop front which runs anti-racist (bourgeois Lebanon has a foreign maid problem) and anti-sexual harrassment campaigns. It also serves food, and sells purses and bags embroidered by Syrian widows. That was one place in which to socialise. There were also the galleries and terrace of the Beirut Arts Centre, where most of the Hay events were held. And there was a city-full of cafes, restaurants, bars and clubs to choose from, the expensive and the cheap, the glitzy and the interesting.

In physical manifestation of the contradictions of the place, shiny new blocks and the mock-traditional streets done up by Hariri’s Solidere are interleaved by pock-marked, cratered older buildings. The old Holiday Inn, notorious site of battle, is left as a grim reminder. We stopped once for falafel in a Palestinian-run cafe on the former Green Line. Somehow the proprieters had stayed open all through the war. The walls on the other side of the road looked like Jackson Pollock, but done with bullets. They looked like the total suspension of social life.

In the hotel lobby I met the lovely Rasha al-Ameer, whose “Judgement Day” is published in English by the American University in Cairo Press. She showered me with books. I ended my four days tired and exhilarated, showered also with friendship and stories. On the last night I had only three hours sleep. Too much was going on at Zico House. AUB students, journalists, publishers, film makers, poets and academics were talking and sometimes dancing. I discussed otherworldly experiences with Miguel Syjuco, whose novel “Ilustrado” is very highly regarded; and Latin American literature with the articulate and snappily dressed Oscar Guardiola-Rivera, author of “What if Latin America Ruled the World?”; and the future of Syria with Asne Seierstad, war correspondent and author of “The Bookseller of Kabul.” Palestinian poet Najwan Darwish and I celebrated our mutual love of the Iraqi writer Hassan Blasim.

“Paris of the East?” I snorted as I swayed down Hamra at four thirty am. Lebanese of multiple styles were still clustering. Someone sat on a step and strummed a guitar. “Beirut is much more fun than Paris.”

Published on Qunfuz here