In No One Prayed Over Their Graves, faith and politics intertwine with the personal in a tale of friends and family across generations.

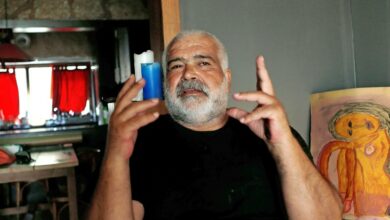

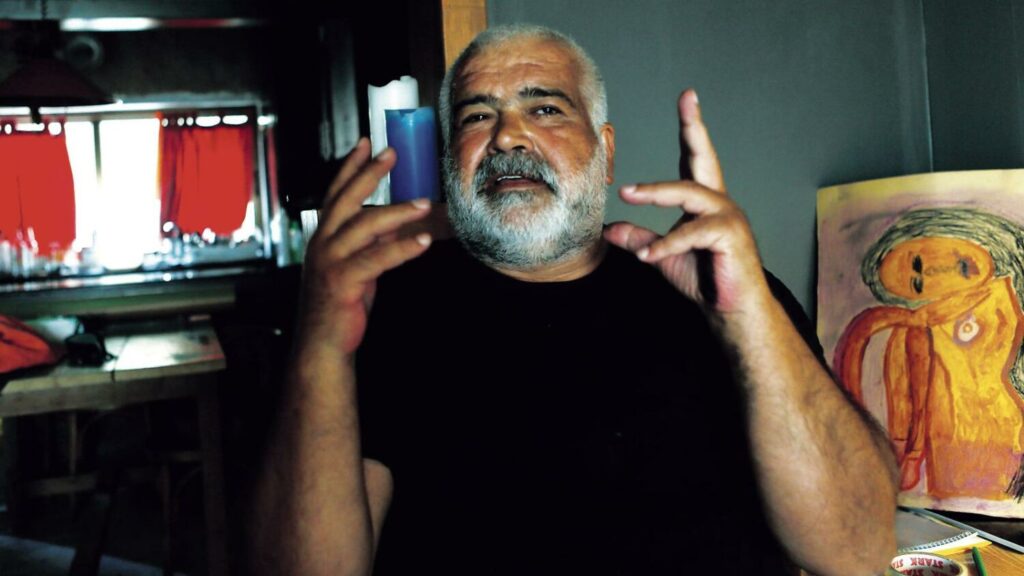

Syrian writer Khaled Khalifa has refused to leave his Damascus home, despite the dangers of an ongoing civil war. Instead, he has steadfastly remained in situ working for more than a decade on his fourth novel, a strange yet epic tale of pleasure, pain, violence, heartache and love.

No One Prayed Over Their Graves begins in 1907 in the small village of Hosh Hanna outside Aleppo, when a massive storm results in the river breaking its banks and destroying the settlement. It drowns everybody there aside from two women, Mariana Nassar and Shaha Sheikh Musa. They survive by clinging desperately to the trunk of a walnut tree while the bodies of their families, friends and neighbours float by.

Two of the village’s best-known inhabitants, Hanna Gregorius and Zakariya Bayazidi, are out of town and rush back as soon as they hear the news. Zakariya is Shaha’s husband, a prominent businessman and horse trainer from a wealthy Muslim family in Aleppo.

Hanna is the village’s main benefactor, a Christian orphan who was taken in by the Zakariya clan and raised as one of their own after his own family were butchered during violent religious riots that rocked the city 26 years ago.

The two friends are devastated, both having lost their young sons in the flood. Hanna’s wife was also among the victims. After spending days helping to recover the bodies and give them a proper burial, their reactions begin to differ.

Zakariya returns to his familial home in Aleppo with Shaha, determined to put the horror behind him and start life over. Hanna insists on staying in the tiny village, eschewing his former life of opulence and pleasure for the simple existence of an ascetic. Then a dream tells him to build a monastery with Mariana, the disaster’s other survivor.

Khalifa’s prose is beautifully sparse, occasionally verging on the poetic as he describes how “the scars of loss had infiltrated Shaha’s soul”. At the same time his writing remains plain and unsentimental, recalling the brilliant Elif Shafak at her most powerful.

He recounts horrific events that have heartbreaking consequences for both these men, as well as their friends and families. Together they make up a memorable cast of characters from all walks of life in early 20th century Syria, then still part of the Ottoman Empire.

Khalifa’s narrative skips backwards to the years before the flood, when Hanna and Zakariya alongside their comrades William Eisa and Azar ibn Hayyim Istanbouli become the talk of the town. This is initially via their teenage escapades involving knife fights and brothels, then subsequently through an ambitious building project.

The quartet combine their finances and talents to design and develop a pleasure palace entirely for the use of themselves and their allies. Dubbed the citadel, it is a symbol of decadence and debauchery that brings the conservative eyes of the city’s religious leaders upon the four friends.

Faith and politics intertwine with the personal, as Khalifa draws on real-life events such as World War I, the Armenian genocide and the Russian Revolution to shape the lives of these characters. While he never expressly condemns the zealotry of any particular persuasion, it becomes obvious that extreme beliefs don’t usually result in happy outcomes.

William Eisa falls in love across the religious and class divide, throwing “a lit match [that] would end up burning down the city”. Hanna becomes ever more convinced to retreat from a world that insists on trying to turn him into some kind of saint, a former fornicator who has found redemption through great suffering.

We watch in frustration as Hanna spends a lifetime turning away from Zakariya’s sister, Souad, whom the reader recognises as his spiritual soulmate. We also follow these people’s sorrows into the next generation, as their children deal with the vagaries of fortune.

Like a Middle Eastern Gabriel García Márquez or a Syrian Salman Rushdie, Khalifa weaves a sprawling tapestry that skims backwards and forwards through time. No One Prayed Over Their Graves flies over decades in the blink of an adverb as the fates of Muslim, Christian and Jew become intertwined through friendships forged in the bloodstained streets of a post-earthquake Aleppo.

Published on Business Post here