The poetic and horrific combine in this tale of love and death set in a Syria torn apart by civil war

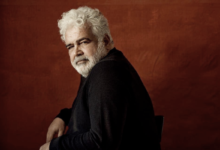

Recently, at a literary festival in Italy, the Syrian author Khaled Khalifa spoke about life in Damascus. “Everyone has left, but a few stubborn souls like me remain. We cling to each other.” Then his face lit up, which happened every time he was about to tell one of his signature anecdotes that mingle defiance with absurdity. Harvard University offered him a highly lucrative fellowship. A few days after arriving there, he began to suffer nightmares. He decided to return to Syria. When he informed the university, they misread him and doubled his stipend. “They couldn’t understand why I wanted to return to a warzone,” he said.

Khalifa is a soulful and perfectly unsentimental writer. This helps fortify his work against glib resolutions and make it more wildly ready for life’s raw light and that unrelenting human desire to live it. Notwithstanding its title, his fifth novel is more about life than death. Leri Price, who has translated Khalifa before, is alive and faithful to the Syrian’s unadorned and direct prose, sentences that often bring together the poetic and the horrific. The title doesn’t quite capture the original, though, which translated literally would be Death Is Hard Labour: by evoking a life sentence, the Arabic title creates a connection between grief and life.

Set three years into the Syrian civil war, the novel’s plot is compellingly simple. Bolbol, the deeply sensitive and conflicted protagonist, has just lost his father. He gathers his two older siblings, Hussein and Fatima, to help him honour their father’s last wish – to be buried in Anabiya, the family’s ancestral village, about 350km north of Damascus. Ordinarily, the journey would take under five hours; if it weren’t for the sad occasion it would be a pleasurable drive, with plenty of nice places to stop and enjoy a good lunch. In the present circumstances, where large swathes of the country have been bombed to the ground and the rest sliced up by checkpoints manned by opposing factions, the passage will be an existential struggle. But the siblings see no other option.

Throughout this diabolical road trip, glimpses of the past lives of Bolbol and his family, with all their imperfect and natural dramas, rise to the dark and unnatural surface of the present, becoming deformed and unattainable. Like the father’s body – which, regardless of the cologne Fatima lavishes on it, continues to bloat, growing darker and more pungent with every passing day – the memory of peacetime Syria appears to be decomposing as it gives way to the present inferno, where the “exceptional had become habitual, and tragedies were simply mundane”.

Bolbol’s real name is Nabil. He was given the pet name, meaning nightingale, by his beloved Lamia when the two were young. He has thought of no one else since, but was unable to act on his passions; now she is married, they are condemned to remain friends. But he “liked hearing others use the same name that [she] used”, and so the nickname stuck. This theme of a life lived with unrequited love is echoed by the father’s backstory, and seems relevant too to the situation that Syria finds itself in, caught between a tyrannical reality and dreams that remain beyond reach.

As they drive with the headlights off, so as to evade snipers, their minibus seems to Bolbol like a big coffin swimming through the night. He reflects on “the numerous coincidences that had saved his life”, remembering that “he even began to act as though fate had taken a special interest in him; when somebody panicked and pushed past him on to a bus, he told himself that being forced to take a later bus was no doubt for the best. The first bus was probably going to be hit by a bomb …” He concludes that, “in war, death is blind”.

The book is interested inthat blindness of fate and the accidental nature of life, as well as the extent to which an individual can sustain his or her ambivalence in the face of a civil war. Confronted with binary choices, doubt is an active position. Bolbol is not for the opposition or the regime. Instead, his main enemy is fear. “Fear had become the only true opposition; it was now each individual versus their own fear.” As with his love, he struggles not to show his fear to Lamia, towards whom “he affected to be careless about his life, as he imagined a brave man might”. He even “began to feel that he was carrying out his father’s instructions solely on her account”. He recalls a moment when “he buried his fear” and attended an anti-regime demonstration with Lamia and his father. It “was like his first orgasm”.

A civil war is a national tragedy, but it is also, and perhaps most poignantly, a personal trial. The most amazing thing about this book is that it managed to exist, that it came to us out of the fire with its pages intact. It is robust in its doubts, humane in its gaze and gentle in its persistence.

Published on The Guardian here