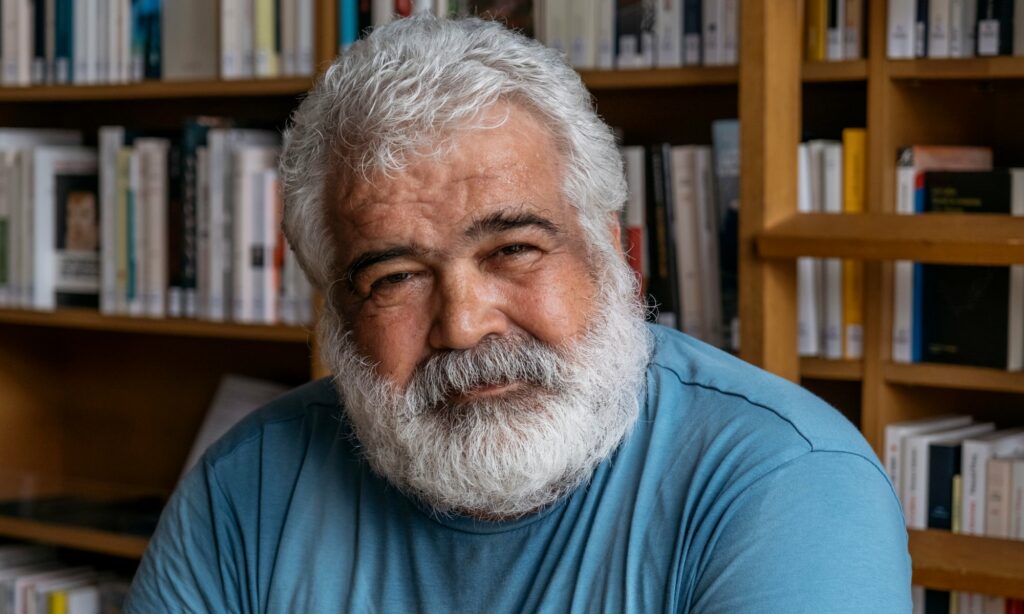

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

He studied and spent his early career in the city, but has lived in Damascus since 1999, one of the few writers who stayed throughout the country’s appalling civil war. He has tried to write about the Syrian capital, he said, but keeps finding himself drawn back to his home city. “After 50 pages, I felt it was not good writing,” he said. “I don’t know the fragrance of Damascus. So I turned back to Aleppo, and I accepted: OK, this is my place. I’ll write all my books about Aleppo. She is my city and resides deep in myself, in my soul.”

While Khalifa was writing his new book, No One Prayed Over Their Graves, Aleppo was comprehensively destroyed in fighting between the Syrian government and rebels. His work is banned in Syria.

Much of this novel is set in Aleppo around the turn of the 20th century. What interested you about this period?

The last quarter of the 19th century was always exciting for me. During these years, the battle of liberals with conservatives or fundamentalists began and here the [Arab] renaissance project began. It did not succeed, but left an impact on the idea of education, libraries, the press, and our thinking about separating religion from the state or reforming religion.

Likewise, the terrible famine that took place around 1914 with the beginning of the first world war, when the Ottoman authorities confiscated everything that could be eaten, leaving millions to starve. The pictures of mass starvation are terrifying. During these years, there was hope for the Arabs to rise up and join the world as true partners, but all that was aborted.

Everything about its culture at that time, such as architecture, music, fashion and journalism, excites my imagination. It was the beginning and the discovery of things such as modern schools and printing. And the aspirations of my city… made me think of the successive losses in our lives, which have not stopped to this day.

How much of the book is history and how much fiction?

I didn’t want to write a historical novel, so the historical research and mistakes were corrected after I finished writing. I didn’t want to fall under the weight of historical fact. It is a novel about lost love, death, contemplation and nature in our lives, about the making of saints, about epidemics, about disasters, about a people’s attempt and struggle to be part of global culture, about the struggle between liberals and conservatives, about the eternal coexistence of this city, about the city at a time when the whole world was seeking to move to a new stage. However, Aleppo was thwarted and destroyed so that it would no longer be part of the contemporary world.

The question today is, who decided that democracy is forbidden to this country?

What do you want today’s Syrians to learn from your portraits of these people and their lives in Aleppo?

I want the Syrians to reread history, and to ask who expelled the Syrian Christians and Jews from their city – who are the children of our country – and who thwarted their great industrial project and their attempt to be part of the civilised world. The question today is, who decided that democracy is forbidden to this country?

By reading this history, I want them to know they are not a group of religious sects, but a people with different and original cultures coexisting. Rereading recent history will help us not to repeat the mistakes of the past by depending on external powers that played in the region since the Ottoman occupation and destroyed its idea of coexistence.

Have you seen Aleppo since it was destroyed?

Yes, I saw the city for the first time since the war, three years ago. It was a devastating moment. Throughout the war, I refrained from watching the videos and many of the photos that were broadcast all the time, documenting the destruction of the city. All the places of my childhood are destroyed, or almost destroyed. After returning to my home in Latakia, I stayed alone for more than four days, crying.

What books are on your bedside table?

I do not read much in bed, but there are always collections of poetry on the nightstand by friends such as Munther Al-Masri, Hala Mohammad, Da’ad Haddad and Charles Simic, translated by Ahmed M Ahmed.

What kind of reader were you as a child?

I discovered books at the age of 10. We are a peasant family with no tradition of reading but, as students, my two older brothers and their friends discovered the books of the left, Russian literature, psychology and philosophy. From that moment, in the early 70s, my personal journey began. I began reading books not intended for children, such as Chekhov’s stories, which I often did not understand at the time. At university I read most of the world’s translated literature and poetry, reread psychology from the point of view of Wilhelm Reich, and opened up to huge works such as Moby Dick and the books of Dostoevsky. The college years were the years of great reading.

Which book or author do you always return to?

Dostoevsky, Gabriel García Márquez, Naguib Mahfouz and Abd al-Rahman Munif. Currently, I feel a longing and desire to read Abu Ala’ al-Ma’arri and Dante again.

No One Prayed Over Their Graves by Khaled Khalifa (translated by Leri Price) is published by Faber (£14.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

Published on The Guardian here