I met Khaled Khalifa in Damascus in the early 1990s, just as his fame as a screenwriter was taking off, and we immediately became close friends.

His career as an author also began around that time, with his debut novel The Guard of Deception. He later started writing series for TV and won acclaim for the popular drama A Portrait of the Jalali Family.

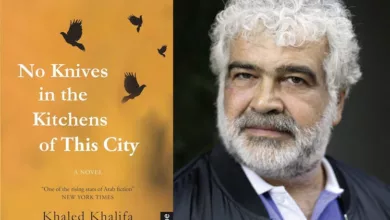

Khaled’s illustriousness was sealed when he won the prestigious Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2013 for his novel No Knives in the Kitchens of This City.

Three years later, another of his novels, Death is Hard Work, about a dead father’s journey to be buried in his home town during the Syrian war, was nominated for the National Book Awards in the US.

But Khaled was celebrated at home for more than his literary work.

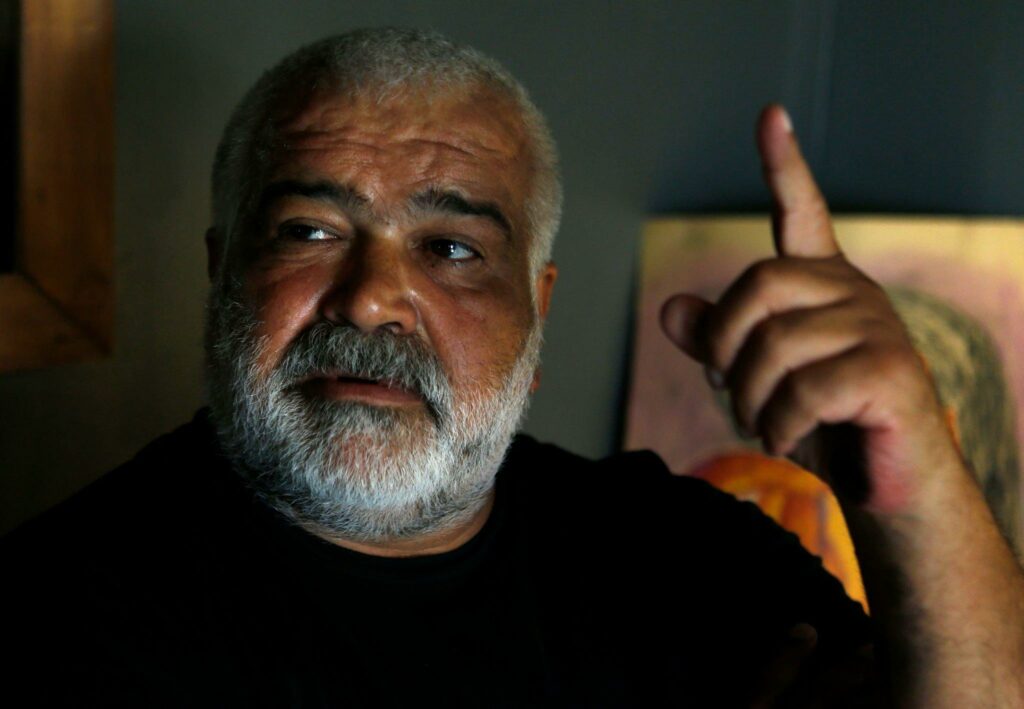

My friend had a larger-than-life personality, which shone when he walked the streets of Damascus, greeting everyone as if they were family members.

Khaled Khalifa was born on New Year’s Eve, something which he said influenced his character and filled him with the joy of life.

With his curly silver hair and dark stubble, he sometimes cut a wild figure, and whatever he did, he did to extremes.

When he drank he got drunk to enjoy; when he cooked, he created a mess around him, throwing together flavours and ingredients till he achieved his perfect dish; when he wrote, the skill with which he brought his characters to life took your breath away.

Khaled was generous to others and enjoyed the recognition his career brought wherever he went, yet he still retained a childlike quality of innocence and wonderment.

Despite his national acclaim in Syria, Khaled stayed principled and his position towards dictatorship and freedom always remained clear.

‘We will win’

When the revolution started in Syria in 2011, Khaled enthusiastically believed that the protests which began peacefully would bring about change.

Sitting in Havana Café in central Damascus, Khaled was convinced that change was imminent.

“I bet that the revolution would start in my hometown, Aleppo, and it would take two weeks for us Syrians to get our freedom,” he once told me.

He burst out laughing. “I lost the bet and I keep on losing,” he said. “But we will not lose hope; one day we will win.”

Even after he was beaten by shabiha (pro-regime gangs) at a funeral procession in 2012 and suffered a broken arm, he remained undeterred.

Khaled was a creator of joy and hope. For the past 10 years, despite his deep sadness about the destruction of Aleppo and exodus of its people, he kept hoping things would change.

He was adamant he would not leave Damascus, where he had moved in the late 1990s. For years, he watched from his window the capital’s suburbs getting bombed and felt helpless about the war.

In 2014, Khaled was invited to be part of a writers’ programme at Harvard University for two years. But when he started there he fell into depression, nostalgic for a Damascus that he could not bear being away from. He quit the programme and returned home.

‘This is my home’

In an interview for a short film I directed in 2019, he told me that even though he felt like an exile in his own country, he couldn’t start a new life somewhere else.

“This is my home, my country, where my mother’s grave lies,” he said. “I don’t want to be somewhere else. I don’t want to create new memories.”

He was constantly worried that he would die as a stranger somewhere else in the world and always wanted his friends to return to Damascus.

On Monday, he was buried in Damascus surrounded by dozens of his friends and loved ones, with a crowed cheering and celebrating his life with tears and clapping.

Khaled touched countless people and will always be remembered for his way with words and for his loving heart.

Published on BBC here