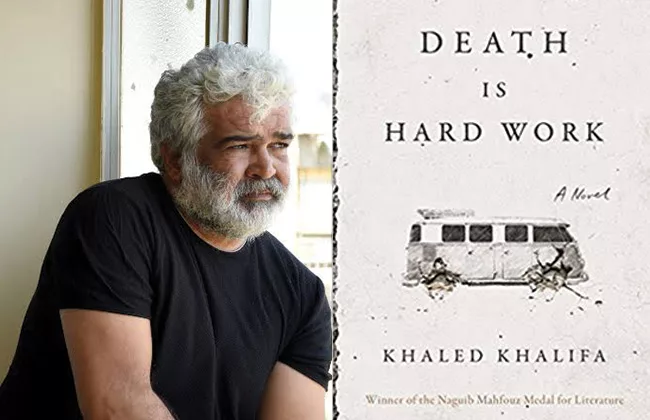

“If you really want to erase or distort a story,” Khaled Khalifa declares in his astonishing new novel “Death Is Hard Work,” “you should turn it into several different stories with different endings and plenty of incidental details.” He’s referring to the salutary comforts of narrative. This — or so we like to reassure ourselves — is one reason we turn to literature: as a balm, an expression of the bonds that bring us together, rather than the divisions that tear us apart.

And yet, what happens when that literature takes place in a landscape where such attachments have been severed, where “[r]ites and rituals meant nothing now”? These concerns are central to “Death Is Hard Work,” which takes place in contemporary Syria and involves the efforts of three adult children to transport the body of their father, Abdel Latif al-Salim, from Damascus, where he has died, for burial in his home village of Anabiya, a drive that would normally take just a handful of hours.

Normal, however, is a relative concept, for the novel takes place in the shadow of the Syrian Civil War, which has rendered even the most basic activities (finding enough to eat, going to work and, yes, burying the dead) into an epic struggle against an all-consuming chaos where anyone can disappear. Death is so pervasive that it “wasn’t even a source of distress anymore: it had become an escape much envied by the living.”

The situation is one Khalifa knows firsthand. Raised in Aleppo, he has lived in Damascus for the last two decades, and a focus of his work is the ease with which norms evaporate in the midst of political upheaval and civil war. His last book, “No Knives in the Kitchens of This City,” which won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2013, also begins with the death of a parent — in that case, an Aleppo matriarch — then interweaves the stories of her surviving family members to develop a kaleidoscopic portrait of that devastated city over 50 years. This new novel is not a companion volume, although inevitably it has echoes, but rather a continuation, a deepening of Khalifa’s engagement with the broken narrative of his country, where for many people, life has been reduced to “a collection of trivial acts that wouldsooner or later have to come to an end.”

That the same might be said of every one of us is part of the point Khalifa means to make. We are all connected by the fragile tendrils of our humanity. But the social order we like to take for granted is little more than a shared hallucination that could go wrong at any time.

Take those siblings at the center of “Death Is Hard Work”: Bolbol, whose deathbed promise to his father initiates the novel’s odyssey; his older brother Hussein, now estranged but once the favorite; and their sister Fatima. There is little that they share in common, other than the accident of birth. “In ten years,” Khalifa tells us, “the three of them hadn’t been gathered in the same place for more than an hour or two during Eid.” Now, they find themselves trapped together in Hussein’s minibus, “[t]aking up their old roles … [which] made them feel less afraid.”

That’s a necessary bit of fiction, something to fall back on as the landscape through which they travel becomes more hostile and intractable at every turn. For one thing, there is Abdel Latif, slowly decomposing in the back. Even more, there is the war, which explodes around them in the form of snipers, air raids, tank conveys, militia waving guns from pickup trucks. Shortly after leaving Damascus, they are detained at a highway checkpoint; “They’re going to arrest the body,” Hussein whispers to Bolbol. It’s a moment of high absurdity, hyperbole even, except it isn’t — because of the old man’s sympathies, which are not with the regime, there is an outstanding warrant for his arrest.

What do you do when you find yourself in a situation where a corpse can be arrested, where even the fact of death is not enough to offer absolution or reprieve? This is one of the questions posed by the novel, and it applies equally to oppressed and oppressor, both of whom are caught with one another in a descending spiral, a gravitational field from which they can’t escape.

“The agent,” Khalifa observes of the arresting officer, “couldn’t seem to make up his mind from one sentence to the next as to whether the state regarded a person as being merely a collection of documents or rather an entity of flesh, blood, and soul.” The agent, and the citizens alike. “The inhabitants of the city,” Khalifa insists trenchantly, ironically, “regarded everyone they saw as not so much ‘alive’ as ‘pre-dead.’”

On the one hand, that’s a defense mechanism: humor so bitter it metastasizes into scorn. On the other, it reminds us of the human core of the novel, and the adaptability, even in this doom-struck landscape, of Khalifa’s characters.

It takes the siblings three days to travel from Damascus to Anabiya, during which time their father’s body literally splits open with decay. The journey recalls Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying,” the long last ride of Addie Bundren; like Faulkner too, Khalifa employs a shifting array of voices and reflections, moving from perspective to perspective, present to past and back again.

The effect is a persistent deepening, as stories are introduced and then revisited, details added through the play of memory. That the most vivid of these narratives — the suicide of Abdel Latif’s sister Layla, for instance, who set herself on fire rather than enter into an arranged marriage with a man she did not love — are also the most private only underscores what the book most wants us to recognize: that the real life of people takes place undercover, in the territory of the heart. Even the fighting is framed through such a filter: “Bolbol reflected that in war, little things … were enough to give you hope: a considerate soldier at a checkpoint, a checkpoint without traffic, a bomb falling a hundred meters away from you on a car that had cut you off and taken your turn in line … Chance has just given us a new life! If that car hadn’t shown up, the bomb would have fallen on us!”

This, “Death Is Hard Work” suggests, is what sustains us, even (or especially) if the public narrative has, like that car, been blown apart. The power of the novel — of all Khalifa’s novels — is that it unfolds within a human context, which pushes against and resists the prevailing social one. What other option do we have? We behave as we must, even if that means going through the motions, we act (to borrow a phrase fromthe late Czech playwright and president Vaclav Havel) as if we are free. “After all,” Khalifa admonishes, “you have to do something if you aren’t just going to lie down and die — if you don’t want to sink down to the center of the earth.”

Published on Los Angeles Times here