From the first, the Syrian novelist Khaled Khalifa scores his latest for full orchestra. The opening page considers the grim aftermath of a devastating Euphrates flood, not far from Aleppo, back in 1907, and it summons every instrument, from tuba to triangle, in a rising crescendo of sorrow:

Before Mariana Nassar lost consciousness, she saw the bodies of her mother, her father, and her four brothers and sisters floating on the river alongside others she recognized: her neighbor and her six children, the rest of her impoverished neighbors. She saw the corpse of Yvonne’s fiancé⎯ the girl was currently in Aleppo having a wedding dress made…. The village priest was smiling as usual, and next to him was Hanna’s son, not yet four years old, and his mother Jospehine Laham, gripping him tightly. Their bodies rose and fell with the waves as if they were dancing.

A dance of the dead, in a one-two of summary and detail: a wedding dress abandoned, a priest’s rictus smile. The bad news arrives at a ringing conclusion, a balanced single-sentence metaphor. A few lines later, too, the morbid music deepens: “an entire life was buried in the river.” Altogether it’s a Wagnerian apocalypse, and soon enough a ghost chorus chimes in, and eventually all these voices combine to sustain four-hundred pages of historical fiction scrupulous in its detail yet breathtaking in its scope, and altogether magnificent.

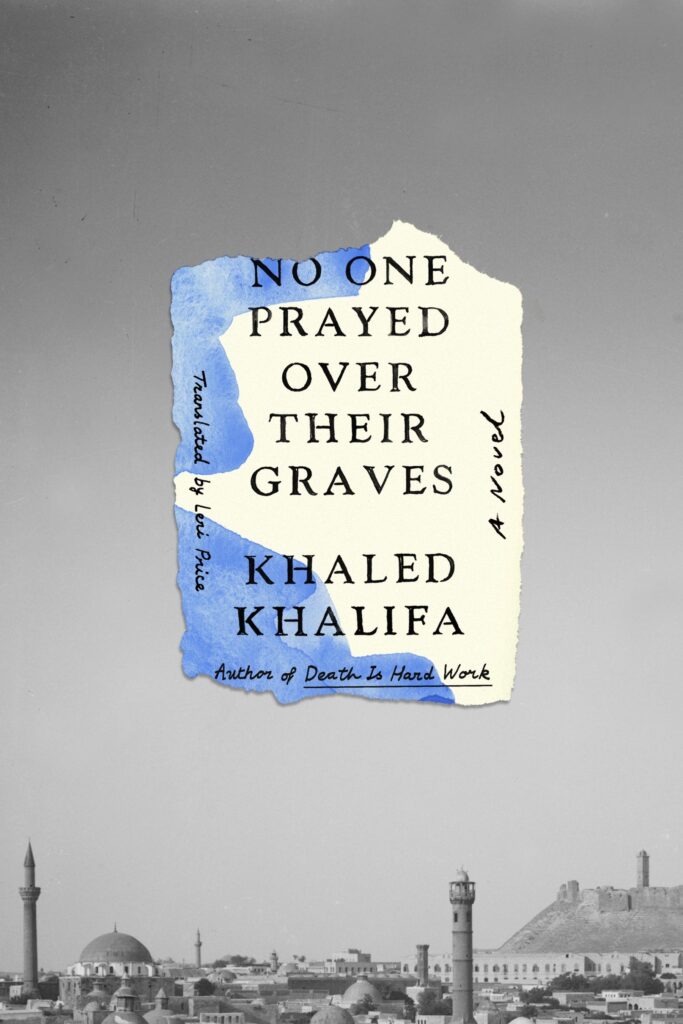

No One Prayed Over Their Graves⎯ translated by Leri Price, who’s also handled the three previous Khalifa novels in English⎯ erupts from catastrophe and follows well-nigh every last reverberation outward. The Euphrates and the Tigris have been unstable since the time of Gilgamesh, but the 1907 flood was one of the worst on record, even leaving much of Baghdad underwater, hundreds of miles downstream. An inciting incident like that frees an author, he might go anywhere, and No One Prayed comes through with revelations and changes at every level of Aleppo society, as well as dramatic turning points off in Istanbul and Venice. These stops and others are on the itinerary for the two men who lost most in the flood, Hanna and Zakariya. Zakariya’s household took in Hanna as a child, after the boy had lost everyone else to violence; the family was Christian, after all. The cross-cultural duo collect a cluster of others around them, the most important Zakariya’s forward-thinking sister Souad and their companion William Eisa, a Jew.

The flood opens the book, but comes roughly at midlife for the characters⎯that is, for three of them. By 1907 religious hatred has cut down the fourth, and such ugly business from the preceding years is often dislodged amid the swirl of the narrative’s first half, while later chapters take the group saga all the way to the 1950s. First we witness the arthritic Ottoman Empire in its final throes, allowing a place for those outside Islam but affording them little protection, and in any case no match for the onrushing locomotive of the twentieth century. Remnants of older cultures turn up as well, fascinating; there’s even a dinosaur skeleton. The fossil that looms over the book’s latter half, however, is that of the flood survivors’ extinct way of life. The First World War takes an especially vicious toll⎯ the Ottomans backed the losers⎯ and the way Khalifa renders Aleppo’s descent into starvation and barbarism call to mind medieval plague illustrations. Thereafter the region falls under a “French mandate,” and the novel has a couple of late scenes dramatizing the calculated indifference of the Europeans: whenever native-on-native hostilities erupt, foreign soldiers turn their back. The West does next to nothing to lessen the antipathy between secularism and fundamentalism, and so loosed the monster that’s lately devoured so much of the Arab World.

A story of such sweep and prolixity would require, for most novelists, at least a trilogy (and for a critic, it’s no walk in the park, either). Indeed, the closest American correlative might be Jane Smiley’s recent trilogy, her Iowa novels The Last Hundred Years (2014–15), with its portrait of a family and community shifting in the political winds. Each of her three novels, however, run longer than Khalifa’s, and his elements are inherently more intense (Iowa hasn’t lately seen a war, much less a religious war). Nevertheless, emotions never feel shortchanged, or crisis points dulled. If anything, No One Prayed suffers the opposite, erupting again and again into cries from the heart and at razor’s edge. The title passage is exemplary: “…the land must be crammed with mass graves where the mortal remains of the wretched had been flung carelessly; no one had buried them, no one had prayed over their graves.”

Not that the novel’s unrelentingly grim. Happy childhoods, or at least prolonged good times, help to shape the principals. Everyone who matters also proves capable of genuine love, though once again, feelings tend to the extreme: “Despite his silence, he was flowing in her blood. She reflected that silent love lives alone, like a wayward, blind child. She felt trapped inside the chasm…” Such oscillations between ecstasy and agony, I must add, set a daunting translation challenge; the rhetoric could easily spill over into silliness. Nonetheless, Leri Price brings off such small miracles repeatedly.

Then there’s the unquiet but ever-rolling river of story. Even when Khalifa finds his Babylon destroyed, he’ll pick up the pieces and begin pulling together another narrative, meandering but alive with fresh mystery. Adding to the vitality is the absence of strict chronology and the switches between points of view, since the story never stays longer than about ten pages with any one central consciousness, and though it most often visits the four I mentioned, several others take a turn, including men and women of other generations, even speaking from the grave. The reading experience ends up a kind of trapeze act, swinging between past and present⎯ a “present” that itself keeps shifting, drawing closer⎯ while seizing hold first of one player, then another. The effect feels exhilarating, if you ask me, though I won’t deny the dizziness. American readers might wish for a genealogy chart or list of characters, as in Smiley, and for a more consistent chapter arrangement. Sometimes we go eighty pages before a break, but once or twice hardly a dozen. Altogether, despite its long-ago trappings and timeless passions, the novel has a distinct savor of experiment. Some of its segues are so surprising, they recall Thomas Pynchon. Ultimately, Khalifa’s latest belongs among the recent surge of norm-busting, story-stretching fiction out of what Frantz Fanon termed, memorably, “the wretched of the earth.”

Fanon’s great denunciation of colonialism dates back to 1961, but the diasporic community he spoke for has grown exponentially, and it’s produced no end of inspiring new authors. Nearly all live and work in exile, like the 2021 Nobel Laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah, born in Tanzania but building a career in England. Khalifa, however, presents a knottier case. His novels do include protagonists who quit the homeland, including an interesting figure in No One Prayed. Still, most of the story and nearly all its participants keep coming back to Aleppo or Damascus⎯as does their creator. Khalifa’s hometown readers, however, have to hide the book, as they did his previous three. In Arabic, he only sees print in Beirut or Cairo. So too, the greatest acclaim has come overseas; his 2016 novel, Death is Hard Work, was a finalist for our own National Book Award. More than that, in a recent interview, Khalifa spoke of concealing his manuscripts and living under a different “official name.” Another recent profile found him in Zurich, on a fellowship, and there too he spoke openly of the Baʿathists’ corruption and inhumanity. He went so far as to compare Syrians to Christ, “bearing their own crosses in the face of adversity.”

Yet he concedes that “he always returns, enduring a sort of exile at home.” Now approaching his sixtieth birthday, Khalifa’s been picking up more and more residencies abroad; a good deal of No One Prayed was written at Harvard, where he lived as one of their Scholars at Risk. At the same time, however, back in Damascus he’s maintained a career in the arts, even achieving some celebrity as a screenwriter for film and TV. An intriguing case.

The author has two early novels, from before 2000, but these remain in Arabic only, and nowadays they too have been suppressed in Syria. Even without seeing those texts, however, I’d draw the same conclusion as Alfred J. Naddaff for Lit Hub: “a disciplined commitment to writing is the only thing that has stayed consistent in his life.”

As for Death is Hard Work and the other two you can find in the States, they stand in contrast to No One Prayed, in that they’re both concerned with present-day Syria, and so just the thing to draw the grim attentions of the Mukhabarat. That Gestapo turns up often in all three books, and their iron rule bruises the women at the center of both In Praise of Hatred (Lebanon, 2008; US 2014) and No Knives in the Kitchens of This City (Cairo, 2013; US, 2016). The first is a torturous bildungsroman, following a young woman first into the resistance and then into prison, while No Knives revolves around a more complicated figure, an ambitious beauty named Sawsan who bucks the system’s machismo, even becoming an Army officer.

Yet though Sawsan earns her bars as a soldier, not a thug, over time she loses heart. Under the present Assad as under his father, the system proves crooked, entrenched in clan loyalties, and the elite families don’t include her own. As her career stalls, what success she might achieve appears more and more dependent on sexual favors; she even confronts the liberties she allowed her teachers, the private lessons that got her into officer school. Not surprisingly, this protagonist ends up one of the very few in Khalifa to leave the country; under another name, in a marriage of convenience, the woman settles in Paris. Still, Sawsun leaves behind several others the novel has followed, among them a gifted yet tragic gay musician almost as remarkable a figure as she.

These thumbnail summaries alone demonstrate how both texts make a natural fit for the same sort of rambling narrative development as Khalifa relies on in his latest. In Praise of Hatred strains with the approach, failing to generate much tension as the major players and their time sequences spiral around each other, but it too stands in contrast with Death Is Hard Work. That one keeps its storytelling linear and its perceptions limited, by and large, to one man, a Damascus office worker named Bolbol. Even the title seems straightforward. The “hard work” is the whole story, as Bolbol, his brother, and their sister struggle to fulfill their father’s dying wish; he’s asked to be buried in his home village⎯ at a time when their country is riven by civil war.

The journey proves no less than infernal, a point underscored by a couple of subtle Divine Comedy references. On the way out of Damascus, soldiers and police stop them repeatedly, waving semi-automatic rifles and demanding first papers, then bribes. Yet beyond the city limits things turn worse, as the trio enters a no man’s land of freelance militias, some speaking Russian and some spouting jihadi slogans. The siblings at least enjoy friendly treatment in the zones held by the rebel Free Army⎯Assad’s outlaws are the family’s angels⎯ but those are limited and haphazard, no more consolation than the blasted rubble of the pilgrims’ hometown. Out there, in fact, the three find themselves close by the Turkish border; they even make an uneasy visit to one checkpoint. Still, even as they feel more deeply estranged, they fall back on their shared ordeal. They complete the roundtrip as strangers, a living embodiment of what military PR terms “collateral damage.”

Both the novels preceding No One Prayed Over Their Graves could be termed the author’s masterpiece, and in my best judgment, this latest makes it three. Moreover, I’d hate to finger any one as “best.” As I’ve tried to show, Death Is Hard Work makes the most compelling read, its structure relatively conventional, but the other two don’t lack for a sense of development, if segmented and incremental. No Knives, given its contemporary setting, doesn’t immediately recall the Thousand and One Nights, that kudzu-tough vine snaking through so much of Arab literature. Nonetheless those loosely linked medieval narratives, so full of women, make a useful comparison. They have an even greater pertinence to No One Prayed.

The new novel, given its cross-century reach, often references the days of the imperial Caliphates. The storied past comes to life whenever one of Khalifa’s characters pokes around old Aleppo, really, a city center that went back as far as any in the world⎯ until it was blown to smithereens by Assad. No One Prayed is plainly intended in part as an elegy, keening and groaning, to that lost UNESCO Heritage Site. Still, it’s another aspect of the novel that most recalls the Nights, namely, the frequency of scenes like this:

Hanna touched her breasts… and kissed her for the first time, on the nipples. She reached for his sex, which was swelling and rising hard, and she felt its veins softly; she… was crying silently when he

Not all the encounters are so explicit, but as Hanna, Suoad, Zakariya, and William Eisa set intricate fractals of relationships wheeling around them, they all give off a lot of heat. As ever, things are taken to the limit, even when couples never connect. Souad doesn’t just carry a torch for her adoptive brother, but rather: “Her soul was crushed, and she wouldn’t grant her body to a man who would be unable to expel Hanna from her depths.” The infatuation eases over time, the woman achieves the same thoughtful maturity as her brothers, but she never loses the old intensity, exactly. Rather, it sprouts more fractals⎯metamorphoses, to cite another ageless story cycle⎯which expand the notion of love. So too, while the affairs and marriages in No One Prayed are all hetero, the alternatives draw occasional mention, and so contribute further to “a fairy tale, full of enough secrets to burn down the city.”

There it is again: cities in ruin, the bleak vision forever shadowing these lives. A reader can’t fail to see the correspondence with Syria’s current breakdown (quieter these days, but by no means settled), and this novel of the past also has people who can’t take the place anymore. One of the book’s better angels, a sagacious priest, emigrates to Beirut and renounces the church, settling down to write books of his own. The case holds up a funhouse mirror, it inverts the position of the priest’s creator and adds to the unease suffered by all these characters. Is their homeland eternally cursed? What’s today’s Civil War, for instance, against the horrors of the First World War? That cataclysm visits about two-thirds of the way into No One Prayed, and three of the protagonists are still alive, bearing witness: “here was death, walking barefoot, creeping … beside me, and harvesting thousands…” The devastation can’t help but prompt an all-too-familiar question: “Who can bury a dead city?”

Yet while the twenty-first-century resonance is impossible to deny, it’s only one element in Khalifa’s larger purposes. His people and their passions will never work as mere stand-ins for contemporary ills, but rather shape their epic as a dialectic between love and destruction. The counterpoint sounds throughout, never simple, not even during the protagonists’ comfortable childhoods. Souad’s and Zakariya’s father isn’t himself aristocracy, but he manages their money, and this leaves him generally laissez-faire. He heads up a household of mixed faiths and he lets the young sow their wild oats. Even when Hanna and others are at their most “riotous,” however, it takes them to ultimate questions: “He liked the moments of spirituality that a woman’s slender body would inspire in him, when he would reflect that she would age and her skin would wither…. His memory [of making love] came back to him, weighted with apprehension.”

Apprehension, visions of death, dog the high times. Hanna can never forget how he ended up an orphan, a nightmarish collision of desire and bigotry: “In 1876, every other member of the … family had been slaughtered … as punishment for the murder of an Ottoman officer who had tried to rape Hanna’s aunt in broad daylight.” Indeed, a similar fatal falling-out, in which heartfelt affection is pitted against the world’s intolerance, spurs Khalifa to a sustained performance at the peak of his skills, a two-part sequence coming about mid-book and running more than a hundred pages.

The chapters are set apart at once, via an author surrogate: “Khaled Khalifa found these works in his family home…” Their original writer was a great-uncle, so we’re told, in a setup that nods again to the Thousand and One Nights, a tale within a tale. As for what happens, the title of the sequence offers an excellent clue: “Impossible Love.” The events mostly take place during the years before the flood, but also continue another few years, and they stay with the novel’s unruly central foursome⎯ until one of them ends up dead. His impossible love becomes one of the novel’s most chilling haunts, it hangs over both his surviving friends and a circle of others, deeply shaken. One of the latter delivers the section to another frenzied outburst, a ferociously imaginative finale that either desecrates or ennobles one of Islam’s most sacred sites.

No One Prayed brings off many, many more such splendid touches, to be sure. The point that matters is how, by stepping back from his homeland’s present torment, after the two preceding works, Khalifa has created a triangulation of viewpoint, profoundly illuminating, and in the process brought off a trio of novels to stand with any similar recent run. Yes, I’d include Ferrante’s Naples quartet among those, but a better comparison might be the brilliant Jokha Alharthi, of Oman. The writer has two very successful books out so far; she won the Booker for Celestial Bodies (Oman 2010, US 2019), and I hope she’s cooking up even better⎯ but in any case, she’ll write it at home, like Khalifa. Oman enjoys a relatively benevolent rule, but it’s a Sultanate, patriarchal; Alharthi must’ve faced difficult compromises, getting where she is, and both her novels feature emigrants. In her case as well as Khaled Khalifa’s we see a duality as rich as that of Stephen Dedalus: on the one hand yearning for exile, on the other forging, in the smithy of their souls, the conscience of their race.

Published on The Brooklyn Rail Here