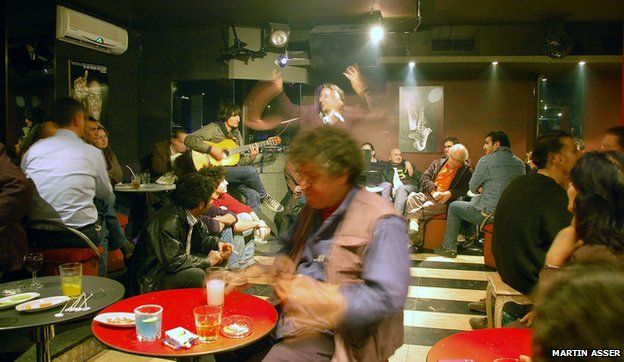

The Firdoss cafe in Damascus was once buzzing with life, but most of its customers have left the city one by one. Among those that remain is a novelist, whose philosophy is to enjoy life, come what may.

There is a table at the cafe which has the same customers every single day. They start with coffee and end up in the evening drinking locally-made arak and smoking the affordable Al Hamra cigarettes made in the coastal city of Latakia.

The four men at this table are almost the only ones left of the old customers in this cafe, which once bustled with Syrians from all walks of life. Music nights, poetry readings, exhibitions, gossip and cultural debate all took place over wine and dinner.

Day after day the crowd diminished as, one by one, the customers disappeared. Some were arrested, others killed. Many said goodbye to this place and its memories. Little by little the music faded and the paintings that decorated the walls were removed one after another.

The table facing the entrance of the Firdoss cafe in the centre of Damascus still has its regular customers – a theatre director, a poet, a musician and a novelist.

Dressed in a red T-shirt over dark blue jeans, with curly silver hair and stubble, novelist Khaled Khalifeh turned 50 on New Year’s Eve.

Every year he celebrates his birthday with his friends, moving from one party to another until dawn. He ends it drinking coffee on Mount Qassioun, watching the sun come up over the city.

But this year he had only three friends to celebrate with. They walked the empty streets of Damascus, ate shawarma and then went home before the clock struck midnight.

He lives in Barzeh, a neighbourhood on the slopes of Mount Qassioun. Behind his house the government has stationed artillery and rocket launchers which it uses to bombard the lower part of Barzeh.

Khaled watches the war from his balcony and often jumps out of his bed when a rocket is fired. One night he saw a neighbour on his balcony cursing President Bashar al-Assad.

“Stop bombing, stop shelling,” he was shouting.

“The man lost his mind,” Khaled tells me with a bitter look on his face.

Sipping some of his arak, Khaled recalls the day the revolution started in Egypt. He was sitting with friends in another cafe in downtown Damascus, the Havana, where all the intellectuals used to gather.

“That night I bet that the revolution would start in my home town, Aleppo, and it would take two weeks for us Syrians to get our freedom,” he remembers.

He bursts out laughing. “I lost the bet and I keep on losing,” he says. “But we will not lose hope, one day we will win.”

Khaled took part in many protests and wrote publicly about his opposition to the Assad regime. Yet when the Americans seemed set to launch an attack against Syria, he opposed it angrily. He told his friends back then: “Dictators bring invaders, but invaders never bring freedom.”

Khaled still believes in the cause of the revolution, even though it has turned into a war that has killed more than 100,000 civilians.

“We have no choice but to continue with all means of resistance,” he argues. “We need to gain our right to live in dignity and freedom.”

Like thousands of other Syrians, he is banned by the security forces from leaving the country. But he does not want to live outside Syria – even now, with the war turning his country into a grim and haunted place.

“I walk in the streets at night and it is dark and there is no-one,” he goes on.

“I shiver in sadness missing the life that has been. Most of my friends have left and my phone hardly rings these days,” he adds.

Khaled is defiant and still tries to enjoy life when possible, drinking, eating, smoking and making love: “I live every day as the last day and I try to enjoy it with whoever is left in the city and with whatever means of pleasure are left,” he says.

But he is constantly saddened by the shelling and killing just across the street from him. There are regular power cuts, shortages of cooking gas and heating fuel. Prices have gone up threefold and there are queues of cars everywhere.

Roads are blocked and checkpoints guarded, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, controlling who crosses in and out. A drive which used to take 10 minutes now takes two hours.

But Khaled feels this hardship has brought people together. “There is no more opposition or loyalists,” he says. “There are just Syrians who are suffering and want to regain their lives.”

Published on BBC here