How ridiculous it is to write you an eulogy, how inappropriate.

The huge outpouring of love expressed for you might be surprising, but the fact is that you always lived by uncomplicated, deeply felt, and steadfast principles. You had a way with innate beauty, a mastery over it that was uniquely yours. So it’s only fitting that we honor you in a genuinely beautiful way, like a tattoo on the palm, or heartfelt words amidst scattered rose petals, or an evening filled with deep emotions and candid confessions to our loved ones.

Goodbyes often feel cold, an expected ritual we’re bound to replay countless times, a bittersweet norm of our lives. Take, for instance, that predictable night in Berlin where we last connected during that pinnacle of clichés – a techno party. My vision was hazy, blurred by smoke machines or perhaps cigarette smoke. Yet there you were, standing by the wall, observing the dance floor from a distance. I parted the fog towards those piercing eyes of yours, gleaming in the dim light. The music was deafening, yet we spoke. When you gestured at my drink, I held up my bottle of water, explaining it was all I drank to maintain my figure. You smirked in disdain. You held the power of ridicule over me, which I had accepted for a long time since the beginning of my acquaintance with you – sixteen, or seventeen years ago. It was against your principles to do anything like that, to be captive to one’s temperament, to diet, to censor oneself, to worry about one’s public image.

These were among the intuitive wisdoms that shaped your life. You’d quickly become frustrated with any hint of self-constraint, even if masked as affection. When we interacted during my early twenties, you constantly encouraged me to prioritize self-compassion, unapologetically, regardless of external judgment or ridicule. You’d often reflect on past criticisms you’d faced, telling critics: “Look, you’ll hear all sorts of stories about me, both good and cringe-worthy, and most of them are true. But your concern should be with the person you see in front of you.”

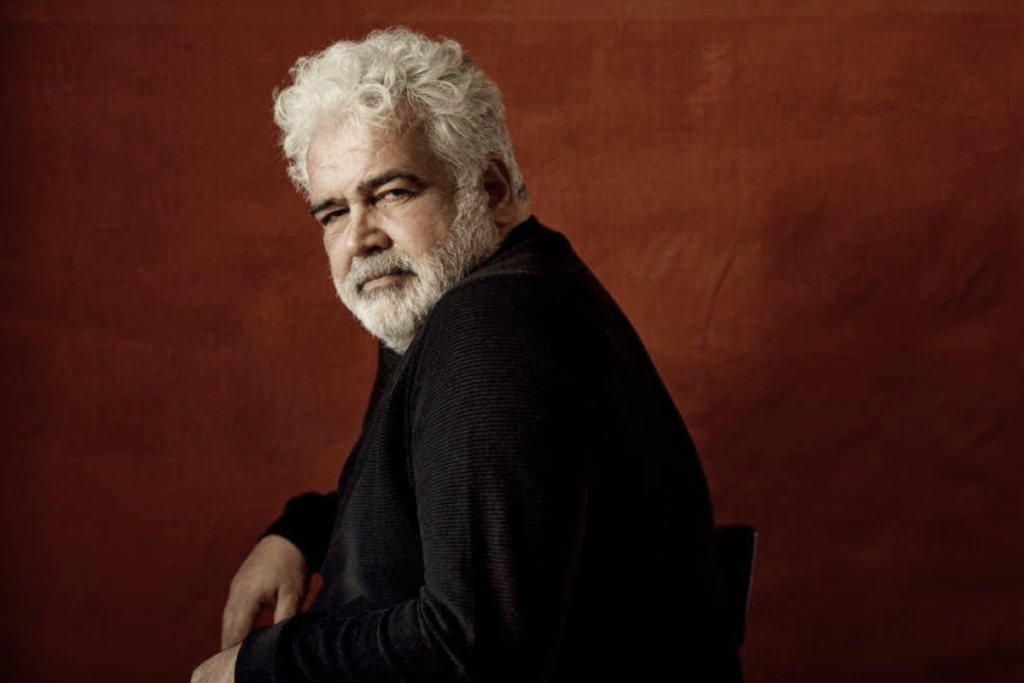

Writing was not something you took as lightly as these playful jabs. People often spotted you engrossed in your work at cafes for hours on end. You didn’t hesitate to review the pieces of budding authors and seasoned writers alike, always keen to share your insights, uplift them, or even chide them for any perceived laziness. This relationship was straightforward, free of any ambiguity or leniency. Out of the blue, one might receive a pointed message from Khaled Khalifa, remarking: “I read something you wrote today that I didn’t like.”

I’ve been on the receiving end of such candidness. Your disdain for reticence and timidity was palpable, not only in your writings but in the way you lived. Your assertive presence in our lives was unmistakable, never seeking permission, always taking the lead. For many of us from my generation, who embraced writing and the arts early on, we fondly addressed you as “uncle” in our regular cafe and bar gatherings. It’s a pity you probably never grasped the depth of gratitude we felt towards this unconventional mentor you embodied for us. You played the role of that rebellious uncle, aiding our escapes from school and parental oversight, being our alibi for those secret romantic outings, all the while instilling in us values that championed our independence. You taught us to break free from societal chains and traditions, to challenge familial and academic norms, and to navigate our love affairs and escapades fearlessly.

Hanging out with you meant embracing the unexpected – striking up conversations with strangers at adjacent tables, what was planned as a quick get-together morphing into a night-long spree across the city, and impromptu sleepovers at your place when it got too late to navigate the myriad checkpoints back to our homes. These gatherings often included a mixed bag of folks we knew, newcomers we’d just met, or even foreign journalists who’d stumbled into our midst, initially intending to record a brief interview with you during daylight hours.

I remember one early dawn in 2012, as the environs of Damascus were choked with checkpoints, I stood outside Kasabji Bar, hoping to hail a cab. Coincidentally, your car rolled by and, recognizing me, you pulled over to offer a ride home. With no ID on me, and in the face of looming checkpoints, I was anxious. You, on the other hand, sported a bandaged arm from a recent injury you sustained on the day of your arrest at Dahdah Cemetery. As we approached the first checkpoint, and before I could betray my nervousness, you leaned towards my window and exclaimed indignantly at the soldier: “Don’t you recognize her? This is the renowned writer Rasha Abbas!”

The guard, although dubious, nodded, feigning recognition, and muttered that he’d “heard the name”. This recurred multiple times on our way, but thanks to you, I made it home without a hitch.

“I was late to the party because I got sidetracked.”

While skimming through some recent notes and quotes, I stumbled upon a random jotting I’d made while reading your novel, No One Prayed for Them: “Bold characters embracing life fully – the author’s biases are evident. From the outset, there’s an appreciation for the daring souls, a sentiment that becomes even more pronounced with mentions of a room in the castle reserved for those contemplating suicide.” Like so many things left unsaid and unfinished, these thoughts remained unpublished, and we never discussed them.

There were countless lessons tucked within the intuitive wisdom you shared. Through you, I came to understand how to handle disagreements gracefully and how to show genuine warmth. I learned that people can grow apart, maybe even become strangers, without either being in the wrong. Whenever we met, whether after disputes or simply years of silence, the first order of business was always kindness and staying true to the principle of “goodness” – but not that stifling one you often railed against.

Life mellowed you out. As the years of turmoil passed, both you and I matured. The longest stretch of time I’d spent with you recently was during a brief trip to the US in 2016. You were at a literary residency in Boston, and I came to see you. I arrived to find you had prepared a huge pot of stuffed zucchini for me, even though by the time I got there, exhaustion was dragging you towards sleep. We managed only a brief conversation where you mentioned how much you missed Damascus, the essence of which you tried to recreate wherever you traveled. Soon after, you retired for the night. Over the next few days, you took on the role of an uncle suddenly given the charge of a niece. Even with your own commitments, you made sure I was taken care of, often ringing up our mutual friends in Boston, Taha and Muhammad, so they would include me in their outings, much like someone finding playmates for a child. Eventually, you cut your stay short and returned to Damascus, a place no amount of casual meet-ups or guests in exile could replace. You went back to your longtime home, where chance encounters on the streets were common and where you hosted gatherings, serving dishes spiced with such fervent love (and hot pepper) that guests were left tongue-tied. You once said you wanted to write a cookbook, always insisting that passion outweighed expertise in the kitchen.

You went back to Damascus, staying true to everything you believed in and penned down. A triumph that didn’t compromise the ideals of liberation, gallantry, and love. You held out your hand to everyone, showcasing your unconditional love for Syria and its people. You chose to stand by those who stayed and those who arrived later, sharing your affection, nobility, and joy – especially the joy, which it was hard for you to bear alone. In your heartbreaking, beautiful exit, you left as the cherished one, the dear departed draped in rose petals, laughter, jubilant songs, and tales of lovers and gallant souls. Even in your absence, we share in the legacy of your fond memory – whether or not there is an eternity in which we will meet you again.

Published on Aljumhuriya here