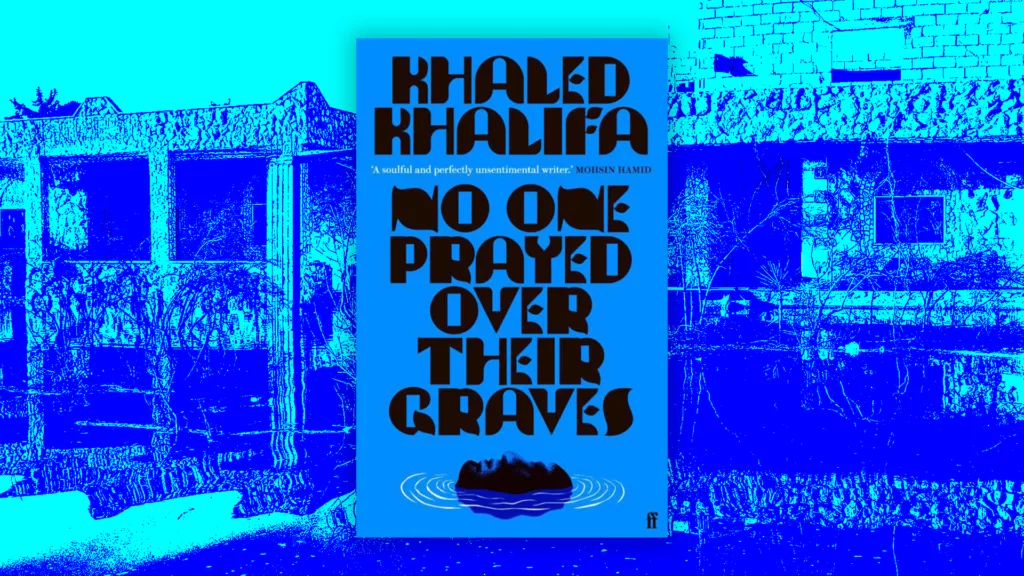

In his latest novel, Khaled Khalifa, a Syrian novelist, and screenwriter, transports us to Aleppine society in 1907. No One Prayed Over Their Graves is an exhilarating, intergenerational epic investigating the human condition, carnal desires, death, and community amongst political and religious upheaval.

The friendship of Zakariya and Hanna binds this narrative’s numerous and vivid threads. Each character is interweaved in their stories creating an evocative portrait of Syrian life under the remaining years of Ottoman rule. Zakariya is from the prominent Muslim Bayazidi family who takes a Christian Hanna under their wing after he is orphaned.

The pair become inseparable, and their lives are permanently and inextricably intertwined throughout the novel.

Khaled’s poetic prose is dynamic and passionate as he imagines multiple characters’ lives, love stories, and psyches against the backdrop of Syria’s complex and traumatic history, which continues to transcend into modern times.

“Khalid’s novel is painfully stirring and prompts sombre introspection. The psychological impacts of war, unrestrained nationalism, and unfettered conflict are indelible. But where there is animosity, there is also love and warm fellowship”

The novel spans over six decades and opens with a devastating flood in the small village of Hosh Hanna. The flood claims the lives of Zakariya’s son and Hanna’s wife and son.

This disaster marks the onset of interminable catastrophes punctuating the rest of the story. The events are elegantly unfolded in the many characters’ consciousness streams. Not quite linear and profoundly breath-taking, we slowly enter Zakariya and Hanna’s childhood which is ostensibly replete with usual childhood mischiefs.

Their innocuous exploits include Zakariya’s younger sister, Souad, a Jewish friend Azar, and a Christian, William. Together the group enters adolescence, and the boys fall into the promiscuous lifestyle of prostitutes and frivolity. They become men obsessed with pleasure, and Hanna soon commissions Azar, an architect, to build the Citadel, a castle-like structure to fulfil all their sensual desires.

The two men and their friends host parties with beautiful women and the best wine. It becomes a legend in the city, and much of the novel refers back to it. This impetuous behaviour saved them from the torrent as they spent the night at the Citadel on that faithful night. The destruction of Hosh Hanna and the loss of his wife and son catalyse Hanna’s new life as a thoughtful mystic.

He becomes tormented with guilt and embarks on learning the meaning of life, attaching himself to nature, and shedding himself of worldly attachments.

The book’s core focuses on Hanna’s transformation and internal discord with religion, war, death, and the societal conflicts that have permeated his life.

But his ruminations and trauma serve as a gateway to understanding the entangled history of the city and the people of Aleppo. The Ottoman Empire is often romanticised for its palatial glory. However, Khaled has chosen to emphasise many of the atrocities and massacres done by the Ottomans, including those against Armenians and Syriacs.

Moreover, Aleppo suffered a number of natural disasters, plagues, and famines throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. So we are introduced to the fates of several characters whose lives become enmeshed and represent this dismal reality. Hanna himself was orphaned because of the 1876 Mardin massacres and lost his whole family at the hands of the Ottomans.

Yet, fate would have it that he is raised by a Muslim family. There is the bleak love story of Aisha Mufti, a Muslim woman who falls in love with a Christian man, William Eisa. Even Hanna and Souad’s crude and forgotten love never saw its fruition, and there are several other sub-stories that the reader is thrust into.

While it is clear that Khaled is a skilled artist who writes with acuity and imagination, the novel feels fragmented and disorienting. The overcrowding of characters, narratives, and timelines made for a lack of fluidity.

The oscillating between consciousness’, histories, and timelines is a very distinct method of storytelling. It is both lyrical and incoherent at times. Hanna’s radical change into a life of asceticism had the potential to be a powerful meditation on a journey of faith, human strengths, and weaknesses.

At times Hanna’s ruminations do prove to be acutely poignant. In the face of destruction and oppression, he realises the futility of it all. A life of sex and glamour was an attempt to hold on to his control, but death and life are bound in the end.

“Hanna’s poetic prose is dynamic and passionate as he imagines multiple characters’ lives, love stories, and psyches against the backdrop of Syria’s complex and traumatic history, which continues to transcend into modern times”

This converging of multiple disparate characters, religions, and their camaraderie is an ode to humankind’s ability toward co-existence and, occasionally, its unfortunate proclivity towards intolerance. The reader is made to witness a myriad of stories in which Muslim, Jewish, and Christians become allies and forge ties for generations. It is a sentiment of unity and peace.

The companionships depicted are tangibly felt and penetrate the heart with hope. However, Khalid’s graceful attempt to portray this sense of community wanes. Many characters with tolerance and friendship seem religious only in name and birth.

Their behaviour is antithetical to the Abrahamic faiths. Those portrayed to be genuinely religious are illustrated as fanatics and parochial. This striking dichotomy fails to acknowledge the nuances in human interaction and the political realities of Syrian history.

Moreover, it is disheartening that the novel’s women, though resilient, quietly resign themselves to the salacious activities of their husbands and lovers. There is no outcry from them for this degradation, and it is even suggested that some of them find it endearing.

While the wars and natural disasters have torn apart families in Aleppo, so have the turbulent tempers and debauchery of the men. There is a deep rift in the families of this story, and at first, it seemed Hanna’s spiritual purging would be a means of healing.

But as the novel progresses, it is clear that the lasciviousness of their youth overshadows all else.

Khalid’s novel is painfully stirring and prompts sombre introspection. The psychological impacts of war, unrestrained nationalism, and unfettered conflict are indelible. But where there is animosity, there is also love and warm fellowship.

We see that this paradox wreaks havoc on the psyche of the characters. Khalid’s language masterfully renders this distress wrought on the mind and society.

While the saga is imperfect in many ways, it is also richly imbued with astute revelations on mankind and Syrian identity. This epic tale will henceforth leave the reader in quiet contemplation, wonder, and even indignation.

Noshin Bokth has over six years of experience as a freelance writer. She has covered a wide range of topics and issues including covering the implications of the Trump administration on Muslims, the Black Lives Matters Movement, travel reviews, book reviews, and op-eds. She is the former Editor in Chief of Ramadan Legacy and the former North American Regional Editor of the Muslim Vibe.

Follow her on Twitter: @BokthNoshin

Published on The New Arab here