In the second of his articles from the Syrian capital Damascus, the BBC’s Martin Asser looks at the role of the cultural life in a police state which for years has oppressively controlled freedom of expression.

I was trying to buy a banned book in Damascus by one of Syria’s top literary figures, and to my surprise it seemed to be going rather well.

The bookseller phoned another supplier located nearby. A boy was dispatched and soon returned with my request, discretely folded in a plastic bag.

Actually, I confess to being somewhat disappointed – as I had been trying to test one of Syria’s famous “red lines”.

These are the taboos imposed by Syria’s repressive government on public discussion of things like politics, the ruling Assad regime, or the security forces.

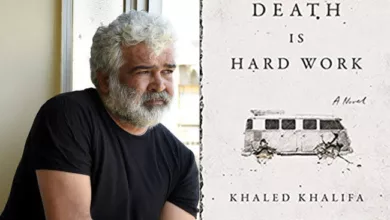

So how was I standing in a bookshop in the centre of the Syrian capital having just bought a book that crossed a whole tangle of red lines, In Praise of Hatred by Khalid Khalifa?

Happily, or perhaps unhappily, my faith in Syrian totalitarianism was restored as soon as I asked for a receipt for my purchase.

“I can’t give you one, sir,” the bookseller hissed conspiratorially. “It’s banned, it’s a banned book. Let me make it out in a different title for the same price.”

Which he did, officially “selling” me a fictional work (in more than one sense) called In Praise of Women.

State of flux

Khalifa’s book may be banned, or at least a tad elusive, in Syria but the author himself is easily accessible, happy to meet for a chat and a bottle of local Barada beer in his favourite cafe in the historic heart of Old Damascus.

“It’s become like a game between us and the authorities,” he told me. “We write what we want and they say what they want. True, my latest novel is ‘not allowed’ here, but you know what they say, books have wings and can fly over any frontier.”

It’s a grey area now. No one knows whether freedom is coming or on the retreat

Khaled Khalifa

In Praise of Hatred, which deals with the rise of religious extremism in Syria, has certainly been hard to suppress. Amid a blaze of publicity earlier this year it was shortlisted for the first International Prize for Arabic Fiction, a competition backed by the Book Prize Foundation.

“At the moment we’re in a transitional stage,” Khalifa said, considering the eight-and-a-half years since President Bashar al-Assad took power following the death of his father.

The initial period after 2000 saw great improvements, he said, but then came a serious backlash, with the low point in 2006.

That was when the authorities arrested writer Michel Kilo and other dissidents who were calling for changes in Syrian policies vis-a-vis Lebanon.

“It’s a grey area now. No one knows whether freedom is coming or on the retreat. The authorities are restricting the internet for example, but on the plus side they are not detaining people who speak out.”

Khalifa is one member of Syria’s artistic community who backs an on-going dialogue with the authorities in the hope of improving the state of freedom of expression in his country.

“The authorities appreciate we are people who are good to negotiate with and we are accommodating – but you know, we get tired. We need hope so we can continue this dialogue and come up with something worthwhile from it.”

Resignation

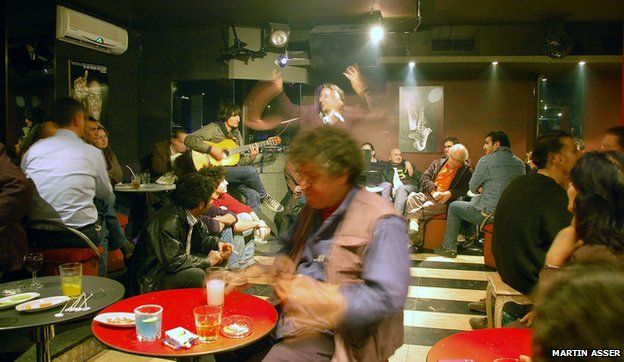

Monday night at the Firdous Hotel has become a bit of an institution for Damascus’s bohemian community: it’s poetry night and local poets and artists gather in the smoky downstairs bar for sometimes raucous, sometimes poignant performances of new and classical Arabic verse.

Late in the session Hala Faisal, a painter and singer, takes the microphone and sings a popular ballad which is greeted with riotous applause.

Faisal has spent most of her life in exile, working in New York and Paris, but she returned to Syria two-and-a-half years ago, hoping to make it her home again.

We met up a couple of days later and full of emotion she tells me that it is time to leave again. She does not want to go into great detail about her decision, but in faltering English she says:

“Maybe because of the politics, they are pushing me to leave. I have to accept some laws that I disagree with, you be within their rules. I have to be honest with myself I cannot just be blind and go on. At least when I go to my bed in the evening I am happy with myself.”

It seems a tragedy for Syria, in the year that Damascus is Arab Capital of Culture, that someone like Faisal feels she has to make that choice: either to close her eyes to the political repression in Syria or pack her bags.

But veteran Syrian documentary maker Omar Amiralai – who for decades has seen his films banned here and around the Arab world – says that is exactly what Syria’s political system is meant to achieve.

The authorities “know that the people don’t really believe their ideology,” he told me.

“The most important thing is that the individual when he stands in front of the regime, the system, the state, shows his obedience and resignation. The idea of revolt or protest disappears from his lexicon.”

Syria may be attempting to come in from the cold diplomatically and politically, but artistically it still has a long way go.

Published on BBC here